Credits

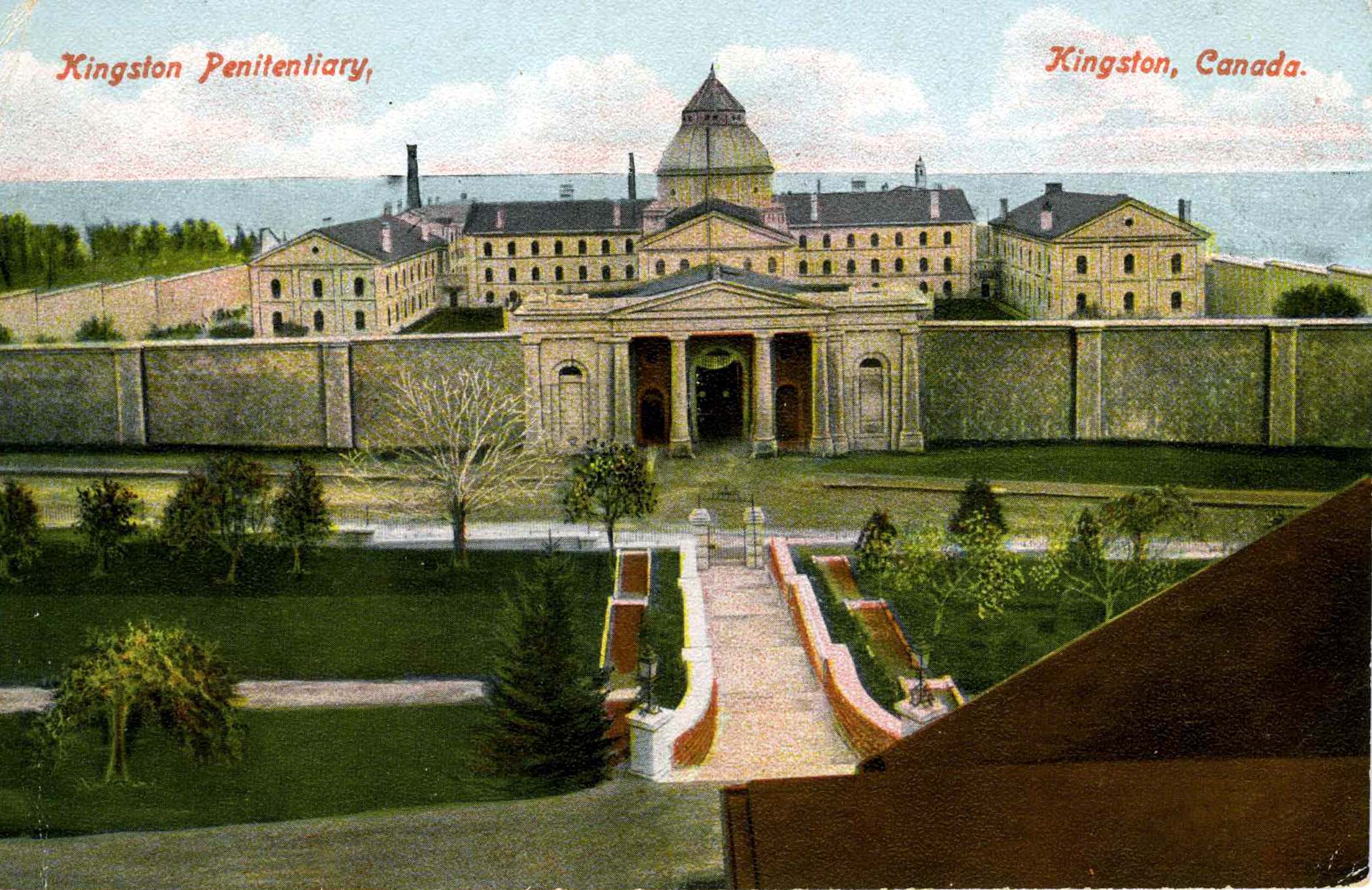

Kingston: Canada’s Penitentiary City

For more than 170 years, Kingston has been associated with criminal treatment in Canada. Beginning in 1835, many offenders of the law, after sentencing by the courts for serious crimes, were sent to Kingston from Upper Canada (now Ontario), as well as convicts from Quebec during the years (1841 to 1844) Kingston was the capital of the United Province of Canada East and Canada West. Kingston became well known for this dark association with punishment. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the parental warning of “Behave or you’ll be sent to Kingston!” became commonplace. Today across Canada, there are 58 federal correctional institutions administered by the federal Correctional Service of Canada and, of these, nine are located in the Greater Kingston area. This represents the highest concentration of such facilities in the country. If one is looking for the birthplace of rehabilitative correctional treatment in Canada, look no further than Kingston!

This tour convincingly makes the case about the great importance of the penitentiary to the Kingston community now and in the past. If we look beyond negative and sensational stories, as well as sad and desperate cases, we see that the operation has provided a livelihood for those families with members who worked or are working for the penitentiary service. It has also contributed significantly to the local economy in a broader sense through business interactions with the many companies providing goods and services to the prison and which purchase or have purchased the varied products manufactured there. Today, the Correctional Service is one of the top three employers in the Greater Kingston area.

Municipal, County and Military Facilities

Kingston was, of course, accustomed to suffering from crime, trying and convicting criminals and maintaining a place for their incarceration. There were cells in the basement of the Kingston City Hall, built in 1844.

James Buckingham described Kingston in his book of 1843, Canada, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and the Other British Provinces:

“Among the public buildings, the [Midland District] Court House is the most prominent. It stands near the center of town, opposite to the principal hotel [the British American] and within a few yards of the English church [St.George’s]. On the upper floor is one of the best-fitted Courtrooms in the province. The Town Jail is in the rear of this Court House (pp. 62-3).”

It was here that a number of the rebels captured at the Battle of the Windmill during the Upper Canada Rebellion of 1838 were held and, in eleven cases, executed. As was the custom, their corpses were interred in the gaol yard.

Many small communities did not have the funds to erect such large and handsome courthouses and gaols as Kingston and Brockville possessed and had to make do with small lock-ups, perhaps containing only one or two cells for a few debtors or criminals in the area. An existing building might be adapted or a new town hall constructed with cells in the basement rather than going to the expense of constructing a purpose-built prison. The Portsmouth Village Town Hall of 1865 (the village is now part of the City of Kingston) had two cells for local miscreants.

Military facilities usually included cells for refractory soldiers or enemy prisoners. Today, visitors can view the prison area at Fort Henry, across the Great Cataraqui River from downtown Kingston. The fort was used to house prisoners as recently and the Second World War.

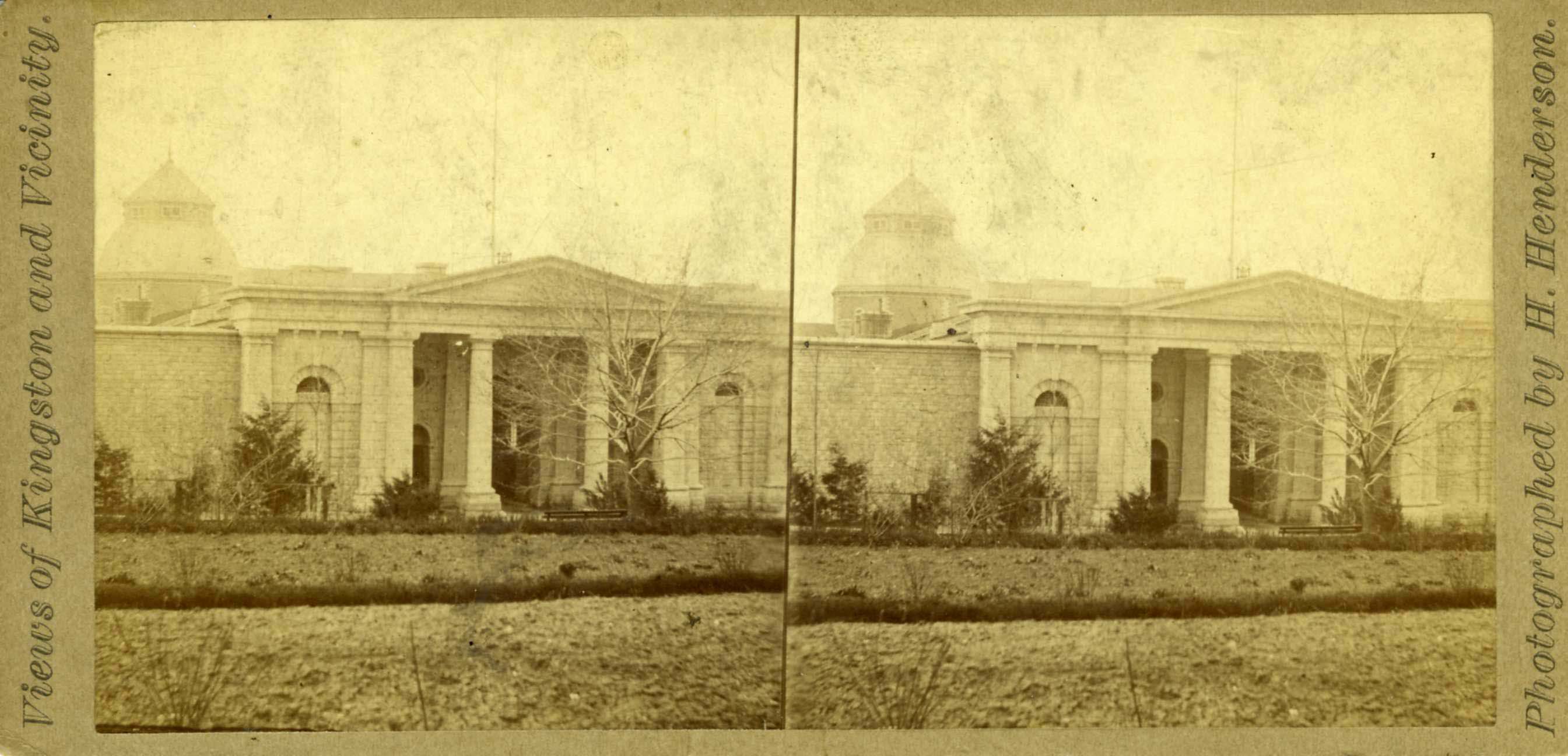

The Origins of the Provincial Penitentiary (now Kingston Penitentiary) in the Late 1820s and Early ’30s

In 1826, the Member of the Legislative Assembly for Kingston, Hugh Christopher Thomson (1791-1834), recognized that the crime rates in British North America were rising at an unprecedented rate due, in part, to a tidal wave of immigration from the British Isles. His interest in penitentiaries was sparked by what he perceived as the short-comings and poor conditions existing in the number of District, or “Common Gaols” (pronounced “jails”), already in operation throughout Upper Canada and Lower Canada. Very few appear to have dealt with any form of rehabilitation or at least it was not central to their operation. In fact, Thomson cited only the Gaol of the Western District, built in 1816 in Sandwich (now Windsor), as coming anywhere close to fulfilling what a penitentiary or even a small gaol should be. In his opinion, the Western District’s success was due to the gaoler’s personal character. Generally, convicts were sent with ease to Common Gaols for their sentences and, in most cases, once there they did nothing but eat and remain idle, until their release.

Thomson knew about some of the well established American penitentiaries, such as the ones at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania and Sing Sing and Auburn in New York and felt that the Canadian government should consider taking this approach to handling the growing problem. Thomson’s theory was ambitious, albeit perhaps naïve. He stated in his report to the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada in February, 1831 that a penitentiary should be:

a place which, by every means not cruel and not affecting the health of the offender, shall be rendered so irksome and so terrible that during his afterlife he may dread nothing so much as a repetition of the punishment, and if possible, that he should prefer death to such a contingency. This can all be done by hard labor and privations and not only without expense to the province, but possibly bringing it a revenue. [sic]

From the early 1830s, the local reaction by certain groups to stories that a penitentiary might be established in Kingston was one of very strong resistance. The argument was not so much fear of the colony’s convicted criminals being brought to the area, but more to do with economics. A significant part of the 19th-century penitentiary experience was the aspect of forced, hard labour. And what would be the result of that forced labour? A flood of products intended, in part, for use within the prison, but also as a means of generating revenue through public sale to offset the costs of operations. Local businesses feared that they would be faced with stiff competition in a limited market, and that this market would be flooded with prison-made goods. And so, when the rumour began to circulate that Kingston was the location of choice for a penitentiary, the idea was met with vocal opposition in the press (reminding one of today’s all too frequent sentiment, “Not in My Backyard”).

Based upon what had been happening since 1818 in the United States at Auburn, New York, and at other American prisons, local tradesmen rightfully felt that the penitentiary would represent unfair, government-funded, competition. The Mechanics Institute of the Midland District even went so far as to form a special committee to travel south of the border to gather information supporting their argument against establishing such institutions in the Kingston region. It was generally acknowledged that penitentiary-made products could be produced in higher quantities and sold much more cheaply than those made by independent tradesmen. Despite this line of thinking, the government continued with the process of establishing the penitentiary. They truly had no other option when it came to dealing with crime.

Why was Kingston chosen as the site for the first penitentiary in Canada? In a word – politics. Plenty of other reasons were tabled to justify the selection, but it really boiled down to political pull, namely that all of the Commissioners, appointed to establish the penitentiary, were Kingstonians.

If one person can be credited with bringing the penitentiary system to Canada, it is Hugh Christopher Thomson, born in Kingston in 1791 to Loyalist parents from New York. His career and life was that of an active, involved citizen as a businessman, newspaper editor and politician. He was also a justice of the peace, militia officer, Warden of St.George’s Church, Secretary of the Midland District Agricultural Society, and Deputy Crown Clerk and Commissioner of the Court of Requests for the district. In his spare time, he was a freemason, an officer of the Kingston Emigration Society, Treasurer of the Midland District School Society, and a generous subscriber to the Kingston Auxiliary Bible and Common Prayer Book Society. Mr. Thomson was a busy man!

At age 28, in 1819, he became the proprietor and editor of the weekly journal, the Upper Canadian Herald, which was a rival to the Kingston Chronicle, published by John Macaulay — the same John Macaulay who would later join him as a Commissioner appointed to establish the penitentiary. Thomson was chosen to be the penitentiary’s first Warden but it was not to be: his chronic poor health and weak heart led to his premature death at age 43 in 1834.

Penitentiary Commissions

Laying the Groundwork: the Penitentiary Commissions from 1830 to 1833

In 1830, the Legislature, finally heeding Hugh Thomson’s suggestion about a new penitentiary, appointed a Select Committee on the Expediency of Erecting a Penitentiary with Thomson as the Chairman. In his first report, submitted early in 1831, he outlined the contemporary practice of how crime was dealt with in British North America, and he presented his argument for the need to build a penitentiary. It was in this report that he first suggested Kingston as the preferred location. He cited the advantages of the existence of the military garrison and extensive fortifications if needed for support, the “healthy situation” on Lake Ontario and the moderately priced real estate. He also suggested that the abundance of limestone found in the area’s “inexhaustible quarries” would afford plenty of employment opportunities for convicts. Revenue was always a primary consideration. As the Kingston trades and craftsmen feared, Thomson suggested that, through the sale of convict-made produce, the government could recoup the costs of incarceration.

With Thomson’s first report accepted, a Commission for the Purpose of Obtaining Plans and Estimates of a Penitentiary to be Erected in this Province was established later in 1831, again with Thomson as Chairman, and with his one-time newspaper rival John Macaulay (1792-1857) as fellow Commissioner. John Macaulay was a local businessman, politician, militia officer and publisher of the Chronicle newspaper. Was it more than chance that two newspaper publishers worked to found the penitentiary? Apart from their good intentions to improve the criminal justice system in Upper Canada and the morals of its inmates, one wonders if they were thinking about the goldmine that the goings-on at the “pen” would provide to the local press!

Thomson and Macaulay submitted a lengthy report in 1832 outlining the results of their visits to existing penitentiaries in the United States such as Auburn, Sing Sing, and Blackwell’s Island in New York and Wethersfield in Connecticut. The report describes in detail what they saw as the merits and the failings of each penitentiary, and included an initial draft of what would eventually become the Rules & Regulations governing the operation. It also provided a very brief account of the international history of penitentiaries; for example, the report states, “the mode of punishment by solitary confinement with hard labour, appears to have been adopted in the Netherlands as early as 1770 . . . .”

Apparently, two sites were considered for Canada’s first penitentiary, namely, Kingston and Hamilton. Both locales offered healthy markets and an abundance of stone; n fact, details were given about the qualities of the stone in each town. Kingston’s “very durable limestone of a bluish colour” and Hamilton’s “Portland free stone of a softer texture” were compared. Some government representatives expressed concern that, because Kingston’s limestone was harder, it would be more expensive to work with — requiring more labour and ruining more cutting tools. Despite this, the momentum continued towards locating the penitentiary in Kingston.

With the second report accepted by the Legislature a third Commission was appointed. The Commission Appointed to Superintend the Erection of a Provincial Penitentiary again comprised of Thomson and Macaulay, along with the addition of Kingston merchant Henry Smith Sr.

During their visits to the U.S., the Commissioners again examined in great detail two penal systems: firstly, the New York “Auburn system”, in which convicts were held in individual cells at night, and worked together in industrial shops in strict silence during the day; secondly, the Philadelphia “Pennsylvania system”, in which inmates lived and worked in complete isolation in individual cells for the duration of their sentences. The Philadelphia cells were equipped with individual exterior yards. In reality, very few “Philadelphia” prisons were actually built because of the expense involved. The Committee selected the Auburn model of prison management, and consulted extensively with the Auburn Penitentiary Deputy Keeper, William Powers. In 1833, their detailed report was adopted, and £12,500 over a period of three years was approved to buy land and erect a building.

On 30 May 1833, the government purchased 100 acres to the west of Kingston and extending north from the shore of Lake Ontario. Purchased from the Pember family, the land had been granted by the Crown to Loyalist Philip Pember, a Revolutionary War veteran of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York. Upon securing the property, the construction of the penitentiary got underway in earnest. Rumour had become reality.

The location was some two miles beyond Kingston’s western border on West Street. This was considered sufficiently “separate and away” to be isolated from the population, yet close enough for conducting business with the community. As the report described:

it was found that no situation combining the advantages of perfect salubrity, ready access to the water, and abundant quarries of fine lime stone could be obtained nearer the Town of Kingston than Lot # 20 in the 1st Concession of the Township of Kingston, which is about a mile West of the Town. The fact that it was considered to be “separate and away” from the populace was also seen as a prudent advantage. The prison’s social misfits would be tucked out of sight and largely out of mind.

Recognizing the unique nature of this type of construction, the Penitentiary Commissioners hired Deputy Keeper William Powers from Auburn Penitentiary in New York to oversee the construction of the complex. John Mills, also of Auburn, was hired as the Master Builder. Day labourers were hired to carry out the actual construction of the penitentiary, as the government felt it would be unwise to entrust the job to a single contractor who might be compelled to cut costs.