Location: Battery Park

Trumpeter swans are the largest of the seven species of swan, three of which can be found in Canada.[1] If you want to spot a Trumpeter Swan you are more likely to see them swimming near Anglin bay but you might see some flying overhead here too. These distinctive birds have black bills and build impressively large, aquatic nests (roughly three meters in length) on existing structures like beaver lodges. Trumpeter swans also have calls that are described as “oh-OH calls” and they are also known to make softer “ooh calls” when trying to find each other.[2]

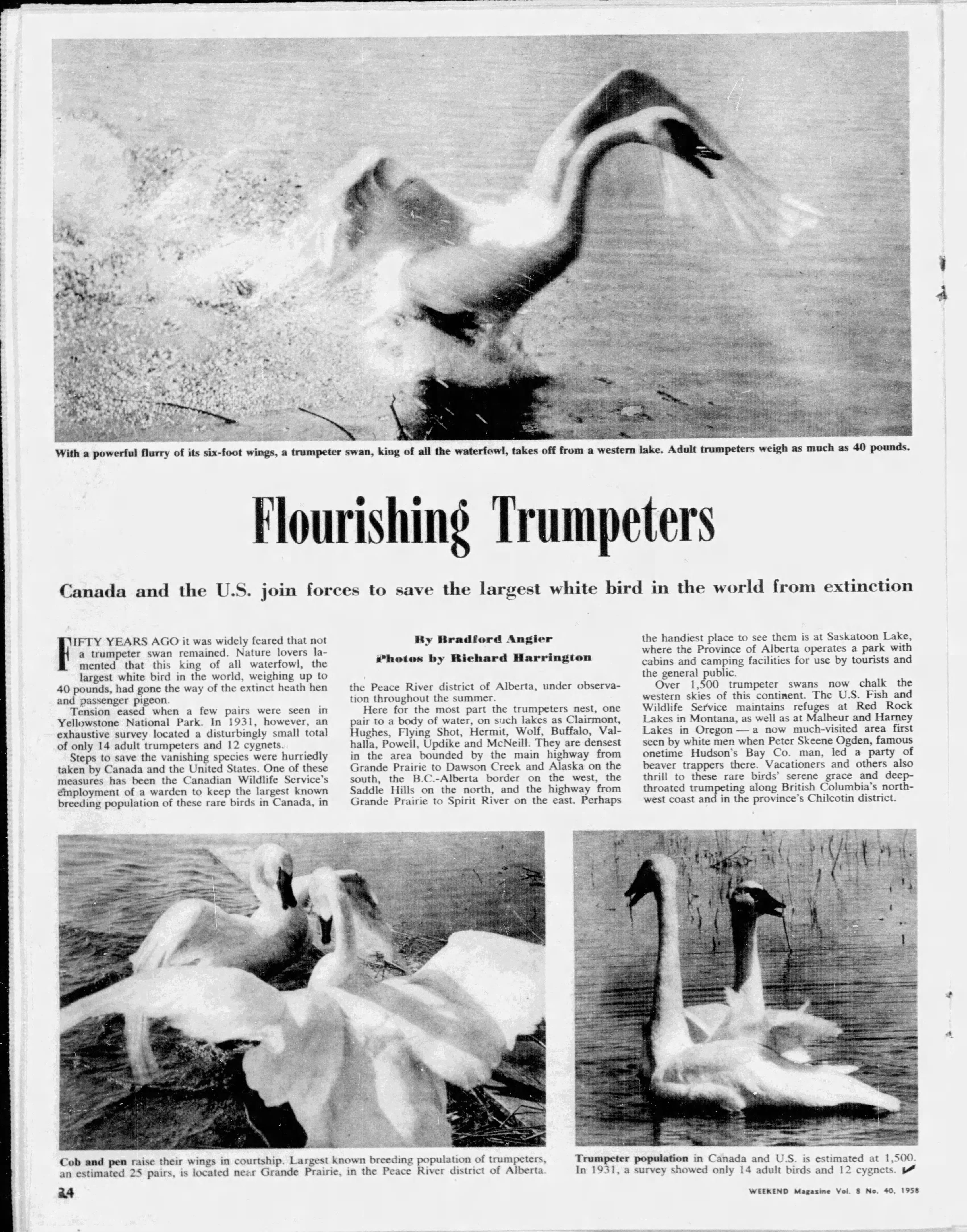

In the early 20th century, North America’s largest water bird and one of the world’s heaviest birds capable of flight was on the verge of extinction. Trumpeter swans were once abundant in Ontario but, like with many wild animals, their numbers dwindled when colonists arrived. In 1916, it was feared that there were only a hundred of them left on the continent.[3] Swans were killed not only for their meat but also for their skin and feathers, which were used to make quill pens and to adorn hats. The last Trumpeter in the province was shot on Lake Erie in 1932. As their numbers declined across the continent, they became something of a news sensation with swan births widely reported on. For example, in July 1963 the Kingston Whig Standard reported that four baby trumpeter swans had hatched in Washington, “the first hatched east of the Rocky Mountains in 80 years.”[4]

The visibility of Trumpeter Swans in Kingston today (not to be confused with the more numerous Mute and Tundra swans) is the result of decades long conservation efforts to protect the species. In 1916, the same year that the species was on the verge of collapse, Canada and the United States signed a Migratory Bird Treaty which greatly assisted in reviving their populations in British Columbia.[5] They were then introduced back into Ontario by Harry Lumsden, a retired biologist from the Ministry of Natural Resources. From 1982 three techniques were used for hatching and raising cygnets who could be re-introduced to Ontario: “1) eggs were placed in the nests of feral Mute Swans on the northwest shore of Lake Ontario for foster-raising, 2) eggs were hatched in incubators and cygnets raised by humans; and 3) eggs were left with captive breeding pairs for incubation and raising of cygnets.”[6] Cygnets raised in the program were held in covered pens at Fair Lake, Metro Toronto Zoo, and the Wye Marsh Wildlife Center for one to two years.

While Trumpeters remain rare in the province, the Trumpeter Swan Society has now released 540 birds in Ontario, and the wild population has increased to 2500-3000, which is considered self-sustaining. This is a particularly impressive achievement when one realises that the birds only start reproducing when they are roughly five years old.[7] It also, however, raises some important questions about the nature of re-wilding. What does it mean to re-introduce animals back into environments in which they have long been absent, for the released animals, for ecosystems, and for the other animals living there? Should humans actively ‘re-wild’ or step back and let animals and ecological processes take the lead? These, and other questions may be answered by ongoing surveillance of rewilded animals, through banding and other technologies, and also through citizen science. Another volunteer run organisation, the Ontario Trumpeter Swan Restoration Group (OTSRG) is helping the resurgence by asking citizens to help identify the swans in the region. You can help by reporting a sighting here, have a look around – can you spot any Trumpeters?[8]

Notes and Credits:

Footnotes:

- [1] These include the native Tundra and Trumpeter Swans as well as the Eurasian Mute Swans.

- [2] “Trumpeter Swans: Sounds” Available from the Cornell Lab

- [3] 9 October 1964, “The Gorgeous Trumpeters.” The Kingston Whig Standard. Page 4. Chronicle and Gazette. Page 3.

- [4] 6 July 1963, “The U.S. Pleased to Announce: Four Bouncy Baby Swans.” The Daily British Whig. Page 12.

- [5] 9 October 1964, “The Gorgeous Trumpeters.” The Kingston Whig Standard. Page 4. Chronicle and Gazette. Page 3.

- [6] Lumsden, H.G., and Drever, M.C., 2002. Overview of the Trumpeter Swan Reintroduction Program in Ontario, 1982-2000. Waterbirds: The International Journal of Waterbird Biology 25(1):301-312.

- [7] Because of the project’s success, Lumsden was awarded the Order of Canada (Thousand Island Association).

- [8] You can access the form to report sightings here: https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScgZbszLDLhb6Fd6gYfgf6atVFLVb7-SJxPPbRtaadolPQXAg/viewform