Street Address: Waterfront Pathway, near Ontario Street

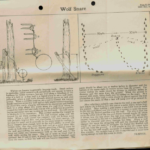

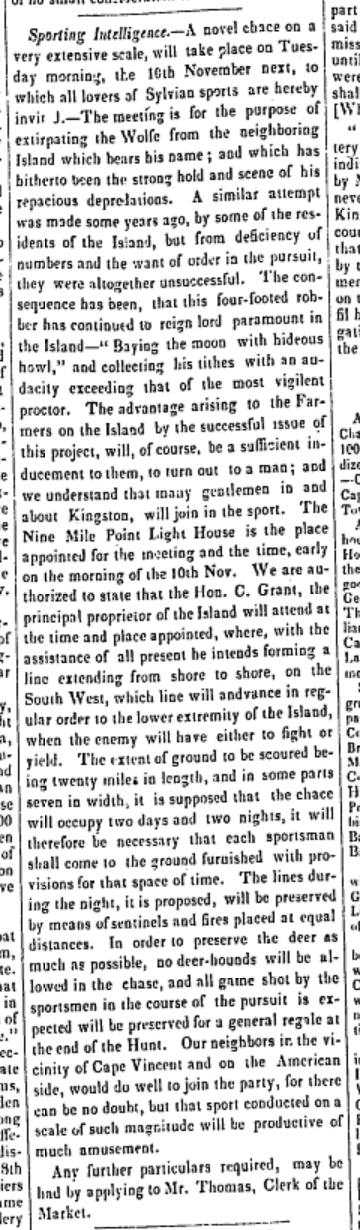

From here you can see Wolfe Island, which stands sentinel where Lake Ontario meets the St. Lawrence River, and the Thousand Islands begin. It is called Kawehnóhkwes tsi kawè:note (meaning “Long Island Standing”) by the Tyendinaga Mohawk, who traditionally hunted deer on the island. The English name, according to official narratives, dates to 1792 when the British changed it from Grande Isle, so named by the French authorities, to Wolfe Island in honour of General James Wolfe.[1] However, as seen in newspaper article from 1835, some people living in Kingston thought it was called Wolfe Island because of a lone wolf who lived there and would “Bay at the moon with his hideous howl.”[2] Based on the number of wolf hunts staged on the Island, it was likely inhabited by several wolves and, as the article makes clear, these wolves often defied and dodged hunters, and evaded capture by hiding in swamps.[3] Indeed, wolves use a variety of sounds to communicate with one another, and their howls can carry up to 10 kilometers,[4] meaning these wolves would have been readily audible from the mainland.

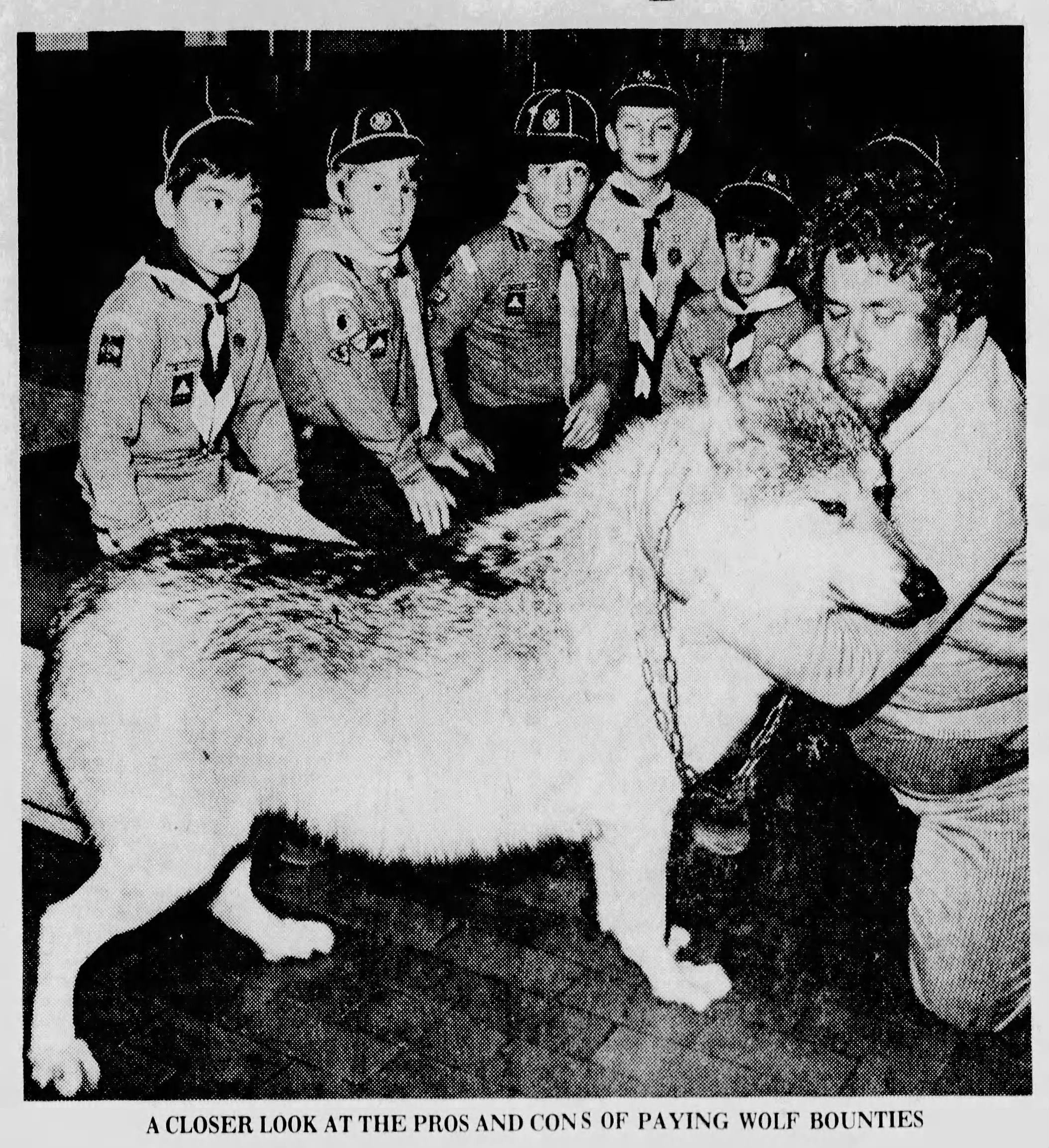

There is a long history of hunting wolves in Ontario. The Provincial Act of 1793 offered four dollars for every wolf head brought into Kingston[5] and by the 1920s the Ontario government offered $50 per head.[6] The justification for killing wolves was that they disrupted farming practices by preying on sheep and lambs and that they were responsible for dwindling deer populations (this despite wolves having lived for centuries alongside deer without having devastated their numbers). Even as wolf numbers were in decline expert hunters and trappers continued to travel to Kingston in hopes of cashing in. By 1927, however, the province was pushing back on calls for increased bounties. In response to Kingston Council’s request for such an increase the provincial Minister of Mines trotted out figures to show that increased bounties did not correspond to more kills. The Minister’s suggestion for more effective wolf elimination was better snares, not higher bounties. Despite capping the bounty this new technology meant wolf kills continued to increase. In the end, wolves retreated far north of Kingston to escape human depredations and are rarely seen here anymore. Are we in danger of re-living this violent history with other carnivores in the area, such as coyotes? As coyote numbers increase in Eastern Ontario let’s hope that science-based co-existence strategies win out over extermination efforts.

This extermination history reveals a fundamental ignorance of wolf societies. Part of the complex social structure of wolf families/packs involves the self-regulation of their reproduction and population levels – having fewer babies when food is scarce, for example. Only the alpha pair reproduce, and the rest of the pack is tasked with raising the pups together. However, if the alpha pair is killed this can have devastating impacts on the stability of the pack. It may cause a pack to splinter and form multiple breeding pairs. Scientists now realize that killing wolves, as has historically been done in and around Kingston, will tend to increase, instead of decrease, populations. The wolf killing industry was creating the very problem it was trying to solve! Organisations like Defenders of Wildlife are trying to move away from archaic hunting campaigns and are instead using guard dogs, flashing lights, and hanging fabric to deter wolves from entering farm territories.[7] Stable wolf families can learn and transfer this knowledge about ‘no go’ zones to the next generation.

Notes and Credits :

Footnotes:

- [1] Hawkins, J., 1967. History of Wolfe Island.

- [2] 12 September 1835, “Sporting Intelligence.” The Chronicle and Gazette. Page 3.

- [3] 4 November 1835, “Wolf Hunt.” The Chronicle and Gazette. Page 3.

- [4] Animal Facts: Wolf. Available on Canadian Geographic

- [5] Macher, A.M. The Story of Old Kingston. Kessinger Publishing. Page 64.

- [6] Ontario offered what was believed to be a very handsome bounty, other provinces offered much less (Manitoba, for example only offered $5 per head).

- [7] “Why killing wolves might not save livestock”, National Geographic, 2014.

Extras:

- Beyond Words: What Animals Think and Feel by Carl Safina

- The Philosopher and the Wolf by Mark Rowlands

- Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservation, book edited by L. David Mech and Luigi Boitani

- Wolf, by Garry Marvin