Period: 1650 – 1700

Fort Frontenac holds an important place in Kingston Francophone, and even general Canadian, history. Originally built in 1673 by Louis de Buade, Comte de Palluau and Frontenac, Governor of New France, the fort stood for almost 100 years and is considered as the earliest permanent European settlement in what is now known as Ontario. Strategically placed at the mouth of the Cataraqui River, at the entrance of Lake Ontario, the fort provided the French with the perfect location to expand their fur trading endeavours, prove their military might to the Iroquois, and block off the English, Spanish, and Dutch expansion into the North. The project for a trading post in the east of Lake Ontario was first started by Governor Frontenac’s predecessor, Governor De Courcelles, and was carried out by Frontenac. Since the king of France, Louis XIV, did not approve of Frontenac’s decision to venture into the interior of the colony to build a fort, because he believed all finances should be put toward reinforcing and protecting existing settlements in Quebec from potential Indian attacks, Frontenac took it upon himself to finance the project without the French monarch’s help. He believed the fort would allow France to extend their territory even further and would provide an established post from where missionaries could convert and instruct the Indians.

Thus, without the king’s approval, Frontenac set out in July 1673 with his men to get his project started. They were met by the local Iroquois in what is now Kingston on July 12th 1673 and construction of the fort began the next day. Within a week, the fort was finished in its entirety, built out of wood, and Frontenac returned to Montreal, leaving behind a garrison of men and René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, in charge. La Salle was an explorer, and Fort Frontenac proved to be the ideal post for him to use as a base for his many explorations. In 1675, after having successfully petitioned for the seigneurial rights to the fort from the king (who by this time had seen the advantages that the fort provided), La Salle undertook a complete rebuilding of the post: the fort now had three stone walls and one wood palisade, four tall bastions, officer’s quarters, a well, and even a cow barn. On the outside of its walls were a small settlement of French and Indian families, as well as a small chapel. However well the settlement at Fort Frontenac was doing, La Salle often used it simply as a resting place between his many adventures in the south. In fact, he was away so often that in 1683 Frontenac’s successor, Governor La Barre, decided to seize the fort under the pretext that La Salle had abandoned it. The king, however, took La Salle’s side and demanded that La Barre return the fort to its rightful seigneur.

For the next few years, the fort served as a warehouse for the fur trade until it was refurbished by the next governor, De Denonville, who fortified it to ensure its safety from Iroquois attacks. The fort served as a prison during the war between the French and the Iroquois, and in September 1687, the Iroquois set a siege on the fort for a month. There was a scurvy outbreak at the fort in 1689, which greatly weakened its defensive power. Because of this, and because the Iroquois were not stopping their assaults on the fort, Governor Denonville sent out an order to have it destroyed and for the remaining garrison to retreat back to Quebec if its commander hadn’t received word to do otherwise before November of that same year. In October 1689, Denonville was replaced as governor of New France by Comte Frontenac, who arrived back in Quebec on the 17th of that month. Upon hearing that his beloved fort was about to be abandoned, Governor Frontenac sent out men to it to attempt to stop its destruction, but alas these men ran into Fort Frontenac’s commander and his men returning to Montreal, having just carried out Denonville’s orders.

In the following years, there was a debate between Frontenac and the French Intendant de Champigny as to whether or not Fort Frontenac should be rebuilt. Frontenac believed it to be an important post both for the fur trade and the defense of the French colony. Champigny, however, argued that rebuilding the fort would be a waste of time and money. Frontenac won the debate in the end and in July 1695 he sent 700 men to have the fort rebuilt. The war between the French and the Iroquois, which was still ongoing during this time, finally came to an end in 1701, 3 years after the death of Governor Frontenac.

Following the Governor’s death Fort Frontenac lost its importance considerably in the eyes of the French, becoming no more than a glorified warehouse for fur pelts, that is until the 1750s, when the British began to pose a significant threat to the French colony. In 1753, the fort’s ammunitions and food stocks were replenished and a garrison of 70 soldiers was sent to help its defense. Though Fort Frontenac served as an effective base for French raids on British forts around Lake Ontario during the Franco-British war, it was not until 1758 that the fort itself was attacked.

In July 1758, word arrived at Fort Frontenac that the British, led by Lieutenant-Commander John Bradstreet, were planning an attack on the Fort. Captain Noyan, commander of the fort, sent a call for help to Quebec, asking for backup to be sent to Fort Frontenac to fend of the impending British assault. Unfortunately for the French, the call for help from Fort Frontenac arrived too late, as reinforcements left Quebec and made their way to Fort Frontenac two days after the British had arrived in their ships not far from the fort in August 1758. Without reinforcements, Noyan could do nothing but surrender to the British, which he did on August 28 1758. It was with this act that the French reign over the Cataraqui region ended. Lieutenant-Colonel Bradstreet allowed the French who still lived at the fort to return to Quebec on the same day as its surrender, and that very night burned the fort to the ground and left Cataraqui.

Though there were some attempts at rebuilding the fort over the next couple of months, these efforts ultimately failed, as the French were still fighting off the British in other parts of Ontario and Quebec. It was with the fall of Quebec City on September 18th 1759 that the French fully abandoned any attempts at repairing the forts they had lost in the war. Fort Frontenac, however, can be remembered as a site of commercial, diplomatic, religious, and military importance in the early Francophone history of Kingston. As Léopold Lamontagne states in his book on the Francophone history of the city, “its ruins that remain visible in Kingston today still attest to its influence in the past.”

Photos: The ruins of the original Fort Frontenac

Photos : Sophie Perrad

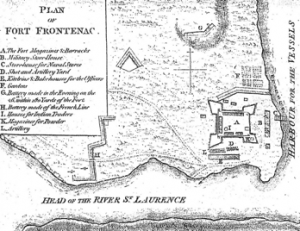

Image : Fort Frontenac en 1758. Source: Canadian Military Heritage

http://www.phmc-cmhg.gc.ca/cmh/fr/image_204.asp