Street Address : 216 Ontario Street

Period : 1900-1950

The Kingston city council met in this handsome stone building, built in 1843-1844. Throughout the first few decades of the twentieth century, the city council struggled with how to respond to the growing numbers of new Chinese citizens and their businesses. Despite institutionalized racism at both the federal and provincial levels, Kingston had no bylaws pertaining specifically to the Chinese. Other cities across Canada including Toronto and Hamilton had bylaws restricting the locations that Chinese people could live and work, creating “Chinatowns”. Although Kingston never passed similar legislation, heated debates occurred on several occasions in 1901, 1909, and 1924 over whether to tax Chinese laundries and restrict the locations where they could operate.

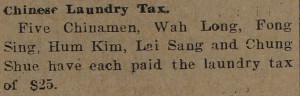

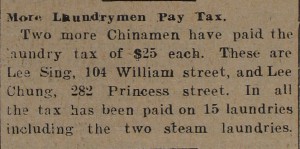

In the spring of 1901, the civic finance committee held several debates over whether or not to add an extra tax of $50 to Chinese laundries. The debates were heated and several members of the committee argued for the tax claiming that the Chinese were parasitic, taking all of their profits and sending them home, making the community poorer. There is no evidence that this tax was ever implemented.

On June 24, 1909, the City of Kingston passed a bylaw that heavily restricted the actions of laundrymen. Laundrymen had to pay a price of $50 per annum for a license to operate their business, they were only allowed to use registered and licensed employees, and they had to apply for a license to change ownership or move to a new location for a fee of $25. Furthermore, they were no longer allowed to live in, or entertain in their businesses and had to keep a separate residence. This bylaw heavily restricted the Chinese laundrymen from operating as “ethnic businesses”, as they had to use only licensed employees and could not pass the ownership of their business on with ease. Finally, the bylaw did not apply to women, who were exempt from every aspect of it. Almost all laundries in Kingston that were not run by Chinese men, were run by non-Chinese women, which shows that the bylaw affected Chinese laundrymen more than any other community.

In 1924, during a debate on an amendment on the bylaw of 1909, a discussion was begun about whether or not a bylaw should be passed that would create a “Chinatown” on the outskirts of the city. A motion was raised and seconded that Chinese businesses should be “put out of town” on the outskirt. Although no law was ever passed pertaining explicitly to the Chinese community, the bylaw of 1909 and the repetitive discussions in city council pertaining to the Chinese demonstrates that an informal form of institutionalized racism did exist.

Kingston’s Chinese population was relatively small compared to many other cities in Canada and thus racism never escalated into large riots or uncontrolled violence, as it did in place in British Columbia, or even Peterborough. Racism however, was still a fact that every Chinese person had to deal with on a daily basis. One incident that was reported by the Daily British Whig was an attack on an unnamed Chinese restaurant owner in 1914. After a short argument a group of young men attacked him in his restaurant.

Besides these specific events the Daily British Whig contained many articles that were derogatory to Chinese people, both in China and Canada. As this newspaper was read throughout Kingston and had a good reputation, it can be assumed that it was influential in shaping the community’s views towards the Chinese population in the city.