Street Address : 200 Ontario St

Period : 1800-1850

In this building, the Elders ran a Saloon, where they specialized in serving fresh fruit and seafood from 1848 to 1859. After James’s death in 1853, Marie continued the business.

James and Maria Elder were the first known black couple to operate successfully a business in early Kingston. We do not know the circumstances of their arrival, but they were already living in Kingston by 1832 because, in that year, their son George Alexander died at age two years and seven months on 23 February.

The Elders realized the value of getting an education. When the movement to establish Queen’s College (now University) in Kingston started in 1840, both appeared on the first subscription list. Most blacks arriving from the United States were illiterate; restrictions were placed on their education in the northern and southern states and in fact educating them was illegal in all slave states except Kentucky. Getting an education was seen as the best way to combat racism and secure better jobs. In 1842 James attended a meeting at Mr. Mink’s, where those in attendance requested that a manual-training school be established in Canada for the “colored population.” He was appointed to a committee formed to establish a “Society for the Improvement of the Colored Population” in Kingston.

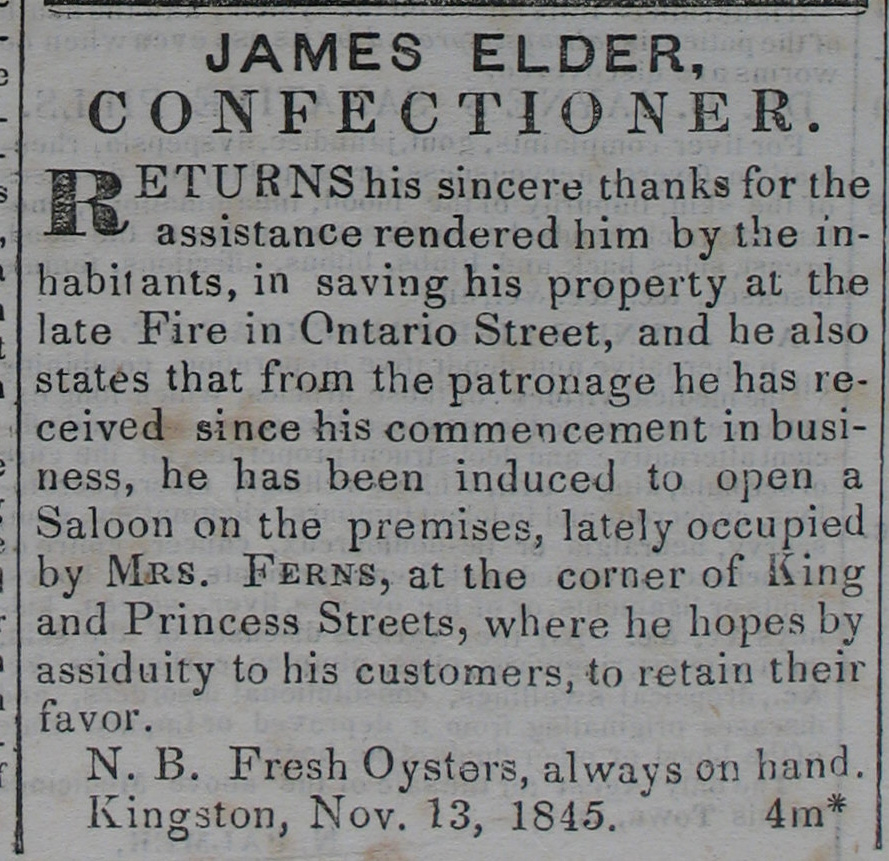

In 1838, the first year of municipal tax assessment records, the Elders were noted as having a store in the First Ward. In June 1844 James announced that he had fitted out the People’s Saloon on the Royal Mail Line wharf, where he hoped to supply “every luxury that the Market affords”. By December he placed an ad in the British Whig to thank his friends and customers for past support and announced that he was moving his Saloon to one of Mr. Hardy’s new buildings opposite Greer’s wharf. In the Victoria House, he would keep constantly on hand a fresh supply of oysters, fruits and confectionary as well as the best liquors and wines. A fire broke out 17 October 1845 in a row of wooden tenements owned by Greer, near his store and wharf. Although the whole range was destroyed, no names were given of the sufferers. A month later, however, we learn that James had been a victim, when he thanked the public for their assistance in saving his property in the late fire on Ontario Street. He added that he had opened a Saloon at the corner of King and Princess Streets, where fresh oysters would always be on hand.

In January 1847, he opened the Oregon Saloon in the brick buildings on Ontario Street opposite the Martello Tower, and next door to Mr. Jackson’s auction establishment (on the corner of Clarence and Ontario). The Whig commented that this “Saloon has been fitted up in good taste, and will, from its advantageous position, do a good business, of which its honest, pains-taking proprietor is truly worthy.”

Disaster struck again a year later, when a fire broke out in Jackson’s premises and spread to Elder’s saloon. James, awakened by his bartender, barely had time to save his wife and children, but lost “his all, the savings of a long life, together with £200 in hard cash laid by” Three weeks later he re-opened the Oregon Saloon in King Street, next door to Mr. Mathieson’s Merchant Tailor’s shop, and opposite Mrs. Willard’s Hardware Store. The Whig was most sympathetic, noting that he had been reduced to poverty three times by the sad effects of fire. In a newspaper ad James gave:

his sincere thanks to the Military, Firemen, and Public, for their vigorous exertions in saving a part of his property from the late Fire. Also, to those philanthropic individuals for the liberal and disinterested manner in which they contributed sufficient funds to enable him to commence in Business again.

The 9 January 1849 issue of the British Whig informed us that he was “once again to be found in his old stand, the Oregon Saloon, in one of the handsome new stone buildings in Ontario Street, recently rebuilt by Mr. Alexander.” (Later this location would long be known as the Prince George Hotel.) Here he could supply the public with fresh oysters, hot and cold lunches and the best wines and liquors.

Being a small business operator meant occasional dealings with local bureaucracy. In April 1851, feeling that the cab stand in front of his premises was hurting business, he petitioned City Council to have it moved back to the old spot near the Court House, then located on the southwest corner of King and Clarence. A new ad in June stated that he could supply customers “with every description of Tropical and Foreign Fruits, Sea Fish and Lobsters; and in season, with Fresh Oysters in shell, daily from the Seaboard.” He also would pack orders in ice and forward them by steamer or stage to gentlemen in the country. In September the Market Collector complained in Police Court that Elder sold a basket of peaches on the wharf and refused to pay toll but the case was dismissed due to lack of evidence. The Market Collector also complained that he had sold fresh fish on his verandah but the judge did not think that the term “open air” used in the Market Bylaw would apply in this case.

The Rev. Mr. Rice officiated at the marriage of their eldest daughter, Mary Maria, to John Jackson on 30 January 1852. But James was not destined to enjoy watching the grandchildren grow up. He died in November 1853 at age sixty-one. The business carried on under the guidance of his widow Marie, who continued to supply her customers with fresh fruit in season, “every new facility for procuring them in the best and freshest condition being readily embraced, and adding to their excellence.” Both the 1855 and 1857 Kingston directories list her as being a “fruiterer”. The British Whig, in one of its famous “Spring Walks,” had nothing but praise for her:

But while we make mention of the more aspiring Saloons and Restaurants, let us not forget our old kind friend, the Widow Elder, who with her Son-in-Law, Mr. Jackson, still keep open “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,”* which flourishes like a young Bay tree. It is to the Widow Elder’s enterprise that the ladies and gentlemen of Kingston are indebted for the luscious Fruits of the South, and the sweet Fish of the Ocean. Here every Southern delicacy can be bought in season, and if not on hand, can be procured at the smallest possible notice. Fresh Salmon, Lobsters, Oysters in shell, Shad and other denizens of the Sea can here be got or ordered; while fruits of a warmer climate are ever to be had in great abundance. We need not recommend Mrs. Elder or Uncle Tom’s Cabin to our readers, for they both recommend themselves.

Marie Elder died in June 1859 at the age of forty-nine after close to thirty years of living and working in Kingston.

James and Marie Elder were shining examples of hard working business people. Despite real or perceived disadvantages of background, despite trials by fire, financial setbacks and family tragedies, they managed to prosper.

* The Elder and Jackson business was named after Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which inspired many to the abolitionist case. It was published as a serial c1851, eventually sold millions of copies and was translated into 37 languages.

Research article :

1844 Announcement in British-Whig, December announcing James Elder salon move post fire. British Whig 13 Dec 1844

1844 Announcement James opening a People’s Saloon on Royal Mail Line Wharf British Whig 25 June 1844

Notice for reopening of saloon post 1845 fire on different premises. British Whig 14 Nov 1845

Notice of 2nd Fire (1848) and ad for reopening of the Saloon on yet another premesis, Whig British Whig 2 Feb 1848 p3

Ad for Oregon Saloon, 1851 British Whig 21 July 1852 p2

Ad in British-Whig (1855-1857) for James’ wife as a “Fruiterer”, carrying on James’ business or article in “Spring-Walk” section British Whig 1855-57?