Street Address : 252 Johnson Street

Period : 1800-1850

In 1841 architect Edward Horsey built 18 attached frame cottages facing Clergy Street between Princess and Brock Street. These were not cottages in the modern sense of seasonal waterside houses but a term often applied to modest dwellings, usually in the heart of a city or village. Horsey’s working-class tenants often included black families.

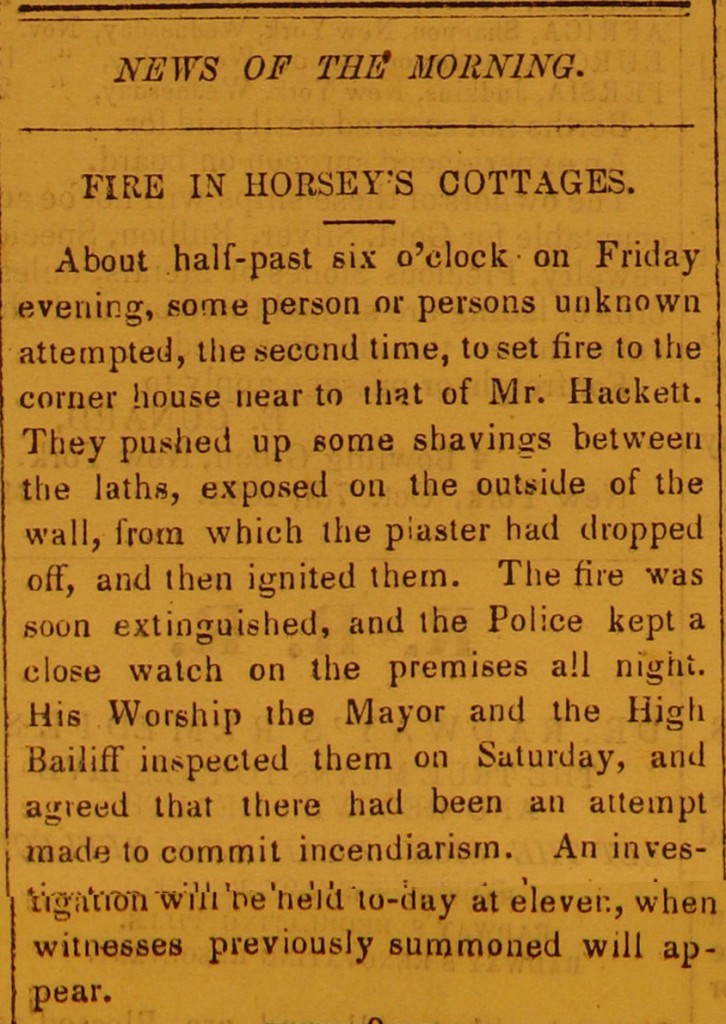

“Fire in Horsey’s Cottages” was the headline of an article in the 28 October 1861 British Whig. Some person or persons unknown had attempted to set fire to one of the houses by pushing up shavings between the laths, from which the plaster had fallen off, and lighting them. The fire was extinguished by a passerby and an investigation was held the next day. It was learned that an earlier attempt had been made on 10 October to burn the same rough-cast house on the south-east corner of Princess and Clergy streets. The testimony of several people was heard, including “Juliana Parker (colored),” wife of Gabriel Parker, who lived in Clergy Street, 4 doors from the corner house where the arson was attempted. No one could think of any person who might have reason to want to harm any of the tenants. The conclusion reached was “that the two attempts made to fire the premises were the wanton acts of malicious persons, without any design to injure the property of any particular person.”

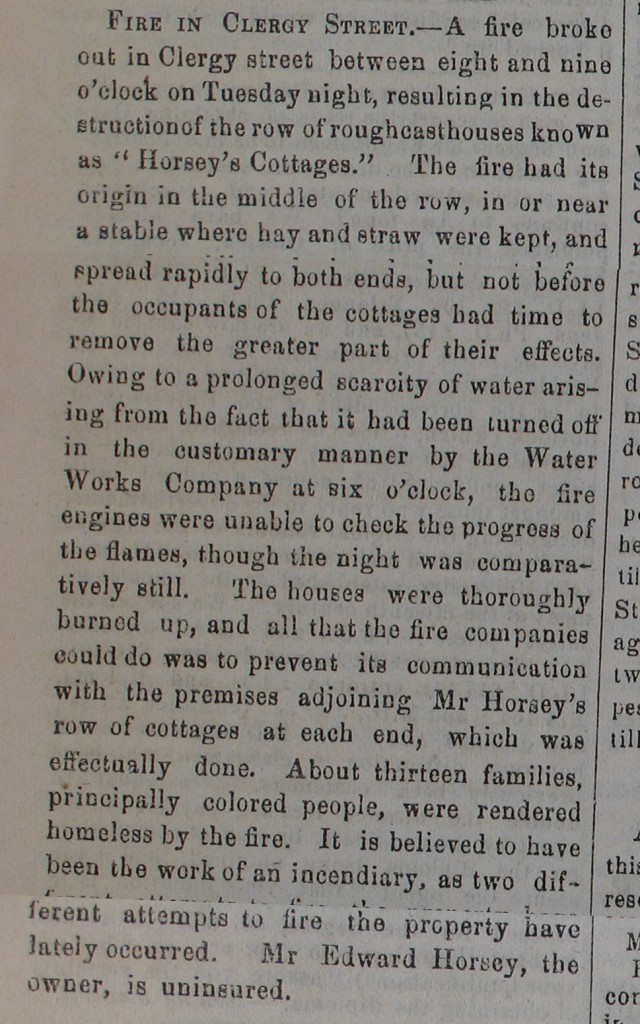

Almost exactly a year later, the Whig used virtually the same headline – “Fire at Horsey’s Cottages.” How the fire started this time was unknown, but it spread quickly along the top of the cottages, which formed a continuous roof without division from one end of the row to the other. A light breeze helped to spread the fire. Most of the furniture was removed, belonging to individuals of the humbler classes, and placed on Clergy and Princess streets. The firemen concentrated on preventing the fire from spreading to the buildings in the rear. “Thus, about fourteen families or more were turned out of house and home.” The Daily News had a slightly different version. “Owing to a prolonged scarcity of water arising from the fact that it had been turned off in the customary manner by the Water Works Company at six o’clock, the fire engines were unable to check the progress of the flames, though the night was comparatively still…. About thirteen families, principally colored people, were rendered homeless by the fire.”

Juliana and Gabriel Parker were already living in the same row of cottages in 1848 according to assessment records of St. Lawrence Ward. (They were both listed as “colored” in the 1861 census, and Gabriel described as a cook.) James Fountain was also living there at the time, along with three females over the age of sixteen. Both he and his wife Phillis are described as “mulatto” in the 1861 census and as “African” in the 1871 census. He was usually noted as a labourer or whitewasher.

The 1862 assessment rolls for St. Lawrence Ward list 12 people who were tenants of Edward Horsey, including Gabriel Parker again, and Presley Ward, blacksmith, who is listed as black in the 1861 Census. Four tenants are definitely white, and the origins of the other six are unclear. So although the News might have been “stretching it” to say that the families were “principally colored people,” it is obvious that there were usually some living in Horsey’s cottages.

Footer 1:

252 Johnson Street is given here as an address closest to the location. This point is one of the two closest intersections to the location of Edward Horseys cottages in the 1840s.